The discourse surrounding the climate crisis has, for too long, been dominated by corporations and the media, which have presented unsatisfactory solutions. However, what could be more comforting than solutions that neatly fit on a convenient grocery list: purchasing organic and local foods, practicing zero-waste cooking, cleaning and maintaining the home with the most environmentally friendly products available, adopting a vegan diet, and opting for cycling or public transportation for all your shopping needs. Don't forget composting, recycling, and educating children to become environmentally responsible citizens. And, of course, the occasional eco-friendly family walk in the fall and spring! To round out this list, you might even consider pursuing a good old housewife's homemaking guide from the 1960s and incorporating a few elements of the neoliberal environmental discourse.

This approach to ecology exerts unwarranted pressure on specific groups, particularly women and queer individuals, as domestic responsibilities continue to be disproportionately placed upon them. These individuals now bear an additional mental burden: caring for what society is actively eroding. Nonetheless, the resources available to them yield minimal tangible impact on the crisis. It's a strategy destined for failure; in fact, these solutions can even create divisions among those responsible for caregiving. That's why we will introduce collective solutions.

Ecological solutions or capitalist tools?

It is neither innocent nor surprising that the environmental struggle is distilled into the management of the traditional family's household chores. The capitalist system seizes the opportunity to offload its responsibilities onto specific groups while seeking fresh avenues to generate profits. Individual actions conveniently align with an emerging concept of responsible consumption, which can be linked to the phenomenon of greenwashing.

In fact, companies facilitate a new means of mass manipulation by establishing a division in consumption: one that is deemed acceptable and another that is not. This message intensifies the pressure on individuals with children, particularly women in traditional households, who are expected to conform to the image of the "good mother/parent" practicing responsible consumption for the well-being of their offspring. We exploit the essentialist attributes of women by conveying the notion that this form of consumption benefits not only the planet but also children.

Divide and conquer: competition and oppression within the environmental struggle

This division further fosters competition among these women and individuals. "Good" mothers/parents who successfully tick all the boxes on the grocery list are encouraged to cast shame upon those who do not do enough. This dynamic frequently intersects with existing oppressive dynamics, as it becomes evident that these "good" mothers are typically individuals with the purchasing power to afford increasingly expensive responsible products. They are often white, cisgender, heterosexual, non-disabled, and affluent women.

Introducing eco-friendly household responsibilities places an excessive burden on these individuals, subjecting them to an unhealthy pursuit of perfection that leaves them utterly drained. This leaves them with limited time for political engagement, further accentuating the already gendered power dynamics within certain organizations. Consequently, they find themselves in a state of deprivation and exhaustion, seeking solace in the perceived impact of these actions, as constructed by popular discourse. Regrettably, there remains little space for fostering solidarity and collective action, which could genuinely empower them to forge a more equitable society where everyone, rather than just privileged women, can wield the power of agency.

Powerless women, men in power

Hence, individual ecology offers a semblance of a solution, appeasing the "female eco-anxious hysteria" in response to the issue, allowing men at the helm of large corporations to continue their destructive practices freely. Consequently, these cisgender white men can absolve themselves of responsibility in the environmental struggle. This is particularly concerning because when environmental responsibility is confined to the domestic sphere and associated with women, it becomes more susceptible to devaluation and ridicule. Consider, for instance, reactionary discourses that uphold the notion that real men must consume meat and drive the most opulent (and polluting) sports cars. This reinforces the capitalist system, which is already responsible for oppressing women and queer individuals, at the expense of both human and natural ecosystems.

Rethinking our struggles: the power of collective action

Nonetheless, there are alternative avenues to explore. Environmental movements can draw valuable lessons from the struggles of racialized communities, which have a rich history of collective organization and a keen focus on identifying the true culprit: the capitalist system that exploits both human and natural ecosystems. As an illustrative example, consider the women of the Chipko movement in India during the 1970s. They orchestrated numerous efforts to safeguard forests earmarked for logging. Their approach involved mobilizing workers and villagers for multiple acts of direct civil disobedience. They undertook forest occupations in Adwani, encircling each tree with their presence, effectively thwarting logging attempts and pushing back law enforcement.(1) Bringing the focus closer to the present, in Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam, women from the Innu community united to collectively oppose Hydro-Québec's power line pylon project. Despite the band council's acceptance of increased funds to permit project advancement, these determined women persisted with their blockade, even in the face of criminalization.(2)

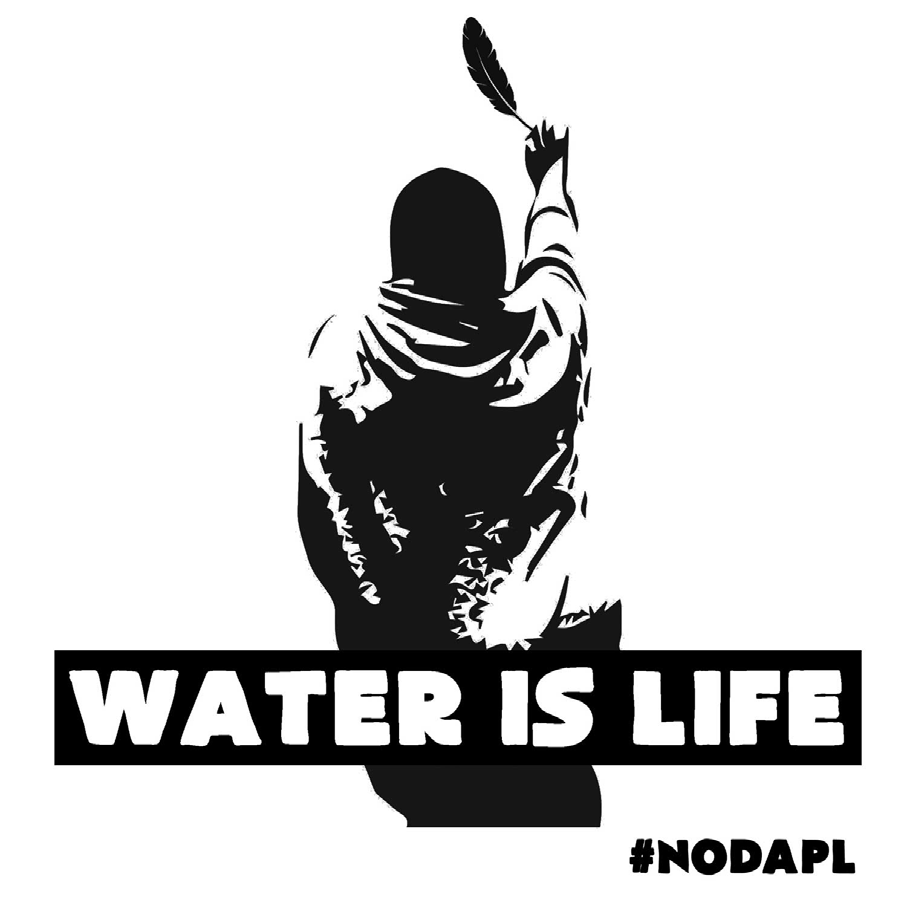

This form of struggle demonstrates the imperative need to address the root of the problem with concrete and effective actions, underlining the necessity of collective action. It falls upon us, collectively, to undertake these endeavors. Simply refraining from purchasing paper or using recycled paper isn't sufficient; we must proactively prevent companies from accessing forests to profit from excessive demands. Merely opting for organic products for our own families falls short; we must unite in organizing to ensure that everyone can fulfill their needs while safeguarding their health and the health of ecosystems. Striving for a zero-waste lifestyle individually isn't enough; we must confront companies that irresponsibly produce waste and reclaim control over the means of production to ensure their use aligns with our needs and respects the environment on which we rely. Mere purchases of electric cars to reduce our climate impact are insufficient; we must compel companies to leave oil untapped by supporting indigenous communities engaged in pipeline resistance.

In summary, we must reposition the environmental issue within the public discourse and democratize the battle, making it inclusive and formidable enough to instigate change in the established order. We cannot accomplish this alone, nor can we do it without collaboration. The environmental struggle is inherently collective, and it should leave no one behind, acknowledging the diversity of circumstances and oppressions. It should provide us with the tools to construct a fairer and more functional society for both ourselves and the planet.

Notes:

1. To find out more, see Vandana Shiva: https://bitly.guru/YYPcE

2. To find out more, see https://bitly.guru/YlHqP