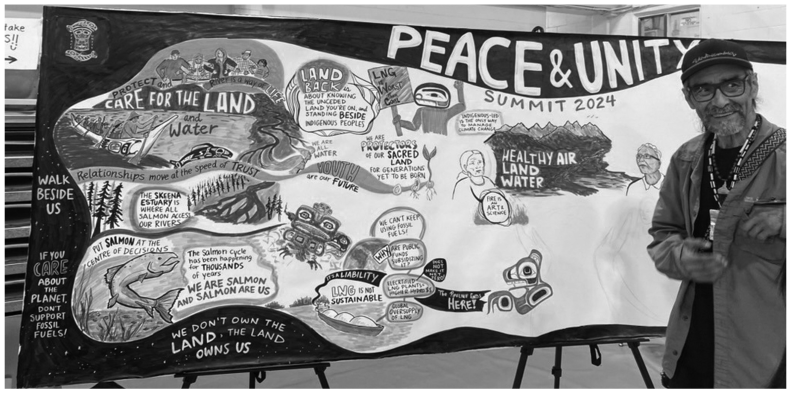

The aim of this article is to critically examine developments in Canadian law regarding the definition of “Indigenous title” (a collective right to land, sometimes referred to as “Aboriginal title”), placing them within the broader history of dispossession. This history has been shaped as much by the economic objectives of the colonial State as by the complicity of its justice system. While acknowledging the progress made by First Nations in the legal arena, it is important to recognize its limits. Today, as in the past, control and possession of land remain central to conflicts involving the extractive industry. In this sense, analyzing history through the lens of ownership provides a clearer understanding of what is at stake today in so-called British Columbia.

Indigenous Conceptions of Territory

The imposition of a European conception of land ownership is one of the foundations upon which colonization was—and still is—based. In many respects, the ideas of absolute, exclusive, and perpetual private ownership [1] of land, particularly the notion that a forest, a lake, or a mountain could be traded, were foreign to Indigenous people. While hereditary rights to hunting territories were (and still are) held by families or clans, rules of reciprocity and kinship systems regulated access to neighbouring territories and their resources. Sometimes, a right of passage had to be paid. Despite this, people did not “own” the land—at least not in the way that a real estate speculator claims possession of land today, or a mining company purchases rights to it. Among the Innu, for example, the verbs used to express the connection to Land convey the ideas of “control”, “management” (tipenitam) [2], “guardianship,” and “responsibility” (kanauenitam). In other words, one cannot claim a territory as one's own unless one knows it, travels through it, and watches over it [3].

This equation between knowledge and control also exists among the Gitxsan. Traditionally, rights to the land are derived from kinship relationships, which extend to other-than-human spirits, such as those of animals, plants, and Land itself [4]. As Richard Overstall, a lawyer and ally of the Nation, writes, these relationships cannot be understood as “property,” just as one does not own their partner or their children: “Yet, in a sense, they are ours, and we are theirs.”

In Gitxsan society, “possession” of a territory exists through what might be described as a “marriage” between the chief and Land. Each chief, at the head of a lineage, inherits a power (the daxgyet) that comes from their ancestors’ relationship with the territory and the spirit that presides over it. According to the story of the Gitsegyukla (one of the four Gitxsan clans), their ancestor, Chief Mool'xan, received the territory from a spirit (naxnox) who appeared to him in the form of frogs. An ethnographer visiting the Gitsegyukla reported the chief's words:

“I grew up in my uncle's house, and my duties and responsibilities were always whispered in my ear while I was still a child. I can now speak from that knowledge. As for my hunting territories, they will be passed on to my successors so that knowledge of them does not escape us. My berry lands will also be used by my successors, and by those who currently have the privilege of visiting them.”

This union between chief and Land is reaffirmed at feasts, which feature song and dance, along with the display of clan regalia. Adaawks, the stories that form the basis of the bond with Land, are also told. Each member of a House (Wilp), through its chief, inherits the right to access the territory and its resources. This right is formalized by the adoption of a name from the Wilp register. In addition to the prestige associated with the name, bearing it also confers fishing, hunting, and gathering rights over part of the common territory.

This example illustrates that, before the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous nations had their own legal systems that allocated rights and responsibilities. Yet for a long time, colonizers denied this reality, either because they were unable or unwilling to recognize the complexity of Indigenous societies. In mainstream thought, private property was regarded as one of the hallmarks of “civilization,” and its absence relegated Indigenous peoples to the “infancy of humanity,” to the status of “primitives.”

Colonial Expansion in Western so-called Canada

Under English rule, the westward advance of the frontier and the establishment of settlers were achieved through force, trickery, or both. Between 1871 and 1921, eleven treaties, known as the “Numbered Treaties,” were signed between various First Nations and the British Crown. Through this process, the British Crown took possession of vast tracts of land, subdivided it, and distributed it to white farmers who settled in what would become Ontario and the Canadian Prairies [5]. At the same time, Indigenous peoples were confined to reserves, over which they held no land rights—the Crown was the sole trustee [6]. Today, it is clear that these agreements were not signed with the full knowledge of the First Nations, that the quid pro quos were largely insufficient, and that many viewed them as a sharing of Land rather than a transfer. Nevertheless, from the perspective of Canadian law, these territories were considered “ceded.” Such treaties were never signed in so-called British Columbia (or in so-called Quebec, for that matter). For this reason, Nations such as the Wet'suwet'en and the Gitxsan inhabit territories designated as “unceded.” This gives their claims particular weight in Canadian courts. We'll come back to this.

What happened on Turtle Island is similar in some respects to the enclosure movement that began in England at the end of the 16th century. Landowners monopolized land that had previously been set aside for collective use, depriving peasants of their source of subsistence—the land, such as what was done to Indigenous people. “They conquered the field for capitalist agriculture, incorporated the soil into capital,” wrote Marx in Book I of Capital [7]. As for reserves, they were created to control and contain Indigenous populations once colonial expansion reached the entire continent. Settlers held the belief that it was only a matter of time before Indigenous people would individually choose to “emancipate” themselves, privatize their portion of the reserve, “civilize” themselves, and thus eventually solve the “Indian problem.” Indeed, the Gradual Civilization Act promised them full access to citizenship in exchange for converting their parcel of reserve land into private property [8].

First Nations Struggles for Territorial Rights

This is not to say that all of this has gone smoothly. Indigenous peoples have consistently defended their collective rights to the land. In fact, the Gitxsan played a central role in one of the first recorded territorial conflicts in so-called British Columbia. In 1872, they blocked the flow of goods along the Skeena River to protest the destruction of the village of Gitsegukla, which had been burned by traders and miners. The resistance paid off, and the Gitxsan succeeded in obtaining compensation for the families. Then, in 1908, the Gitxsan chiefs, who had long opposed mining development on the Lax'yip, secured a meeting with Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, during which their right to ownership of their ancestral territory was discussed. However, in 1927, the Canadian government prohibited Indigenous people from organizing politically to assert their territorial rights, as well as from hiring lawyers to take legal action.

A few decades later, in 1969, the government of Pierre Elliott Trudeau introduced a new policy known as the White Paper. This policy refuted the idea that Indigenous peoples possessed inherent rights, including land rights, while simultaneously attempting to abolish “Indian status.” The stated aim was to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society, which, among other things, involved imposing private property and government economic development programs on them. The publication of the White Paper sparked an unprecedented wave of mobilization, forcing the government to back down two years later.

At the same time, Indigenous peoples were engaged in a legal battle with the government, led by Nisga'a hereditary chief Frank Calder. White settlement in so-called British Columbia, from the 19th century onward, had forced many First Nations, including the Nisga'a, to abandon their traditional territories in favor of life on reserves. This displacement occurred against their will, without any treaty or compensation. The Nisga'a decided to take the province to court, accusing it of violating their rights to their traditional territory [9]. They maintained that their land rights had “never been legally extinguished.” However, the first challenge was to obtain recognition of the very existence of such a right, which judges had reserved for so-called “civilized” peoples. In 1911, Lord Summer, sitting on the highest court of the British Empire, made the following declaration:

“Assessing the rights of Aboriginal tribes [sic.] is always difficult. Some tribes are so far down the ladder of social organization that it is impossible to reconcile their customs, conceptions, and representations of law with the institutions and spirit of a civilized society. Such a gap cannot be bridged.”

In Canada, St. Catherine's Milling and Lumber Co. v. The Queen (1888) legitimized the colonial claim that Indigenous territorial rights were limited to usufruct rights (i.e., the right to use the property of another) and depended on the goodwill of the Crown. As a result, the Nisga'a were required to demonstrate, firstly, that they had indeed “owned” the territory prior to the arrival of settlers, and secondly, that these land rights had not been extinguished or modified by Canadian legislation. Although these remedies run counter to the overt ethnocentrism of the colonial court system, they remain asymmetrical: it is up to the First Nations to translate their relationship to Land into the legal language of the colonizers—the language of the Canadian state. In other words, Indigenous land claims are forced to be expressed through foreign and imposed categories or... remain mute.

The Calder case finally reached the Supreme Court in 1969. At the end of the trial, three judges ruled that Indigenous title to land had been abolished (or abandoned) before British Columbia joined Confederation, while an equal number supported the Nisga'a view that they had never been the subject of a treaty or statute of any kind. In the end, the scales tipped against the Nisga'a when the seventh judge invoked a procedural defect and dismissed the case.

For our purposes, it is important to remember that from Calder onwards, and in all subsequent judgments, it is property (dominium in Roman law) that is at issue, and not sovereignty (imperium). The legitimacy of the Canadian state is never questioned, and it remains sovereign over Indigenous lands. As we have seen, the concept of ownership fails to capture the multiplicity and complexity of the relationships Indigenous people have with their territory and the other human beings with whom they share it.

Despite this defeat, the Calder case, concluded in 1973, sent shockwaves through the legal landscape, as it was the first time the Court recognized the possibility that Indigenous Nations might have a right to unceded lands. As a result, the federal government modified its approach to First Nations' territorial interests. “Perhaps you had more rights than we thought,” Pierre Elliott Trudeau admitted to Indigenous chiefs.

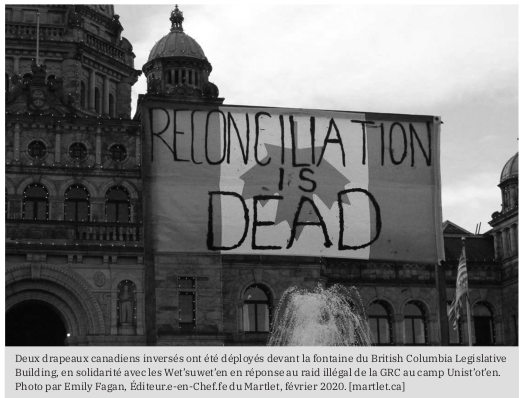

Post-Calder and the Mirage of Reconciliation

This period was also marked by the Oil Crisis and the expansion of extractive activities (oil, natural gas, and ore) in the north of so-called Canada. In response to the growing anti-colonial nationalism among Indigenous peoples (with Red Power in full swing during the 1970s), the government opted for policies of recognition and accommodation, without undermining the colonial structure of so-called Canada. In 1982, when the Constitution was repatriated, Indigenous rights were enshrined within it. “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada [Indian, Inuits and Métis people of Canada] are hereby recognized and affirmed.” stipulates Section 35(1). In 1990, the Sparrow case put these new provisions to the test, confirming the Musqueam’s Indigenous right to fish on the Fraser River. At the same time, the court outlined a set of criteria aimed at clarifying the content of Indigenous rights. This victory, however, was only half-hearted, as the court also defined various grounds on which governments could justify violating these rights. These criteria would continue to be debated in subsequent judgments [10]. Indeed, the B.C. government's refusal to enter into negotiations with First Nations to determine the content of Indigenous title would lead to a number of legal conflicts.

Resistance has continued outside the courts as well. Between 1984 and 1993, the Tla-o-qui-aht and their allies fought relentlessly to protect old-growth forests and prevent the logging industry from gaining access to their territory on western Vancouver Island. The mobilizations culminated in the summer of 1993 with the arrest of 856 people, marking what would be considered the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history until the Fairy Creek blockades in 2021.

During the same period, in response to the provincial government's failure to recognize the "ownership" of ancestral territories, the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en Nations launched a lawsuit known as the "Delgamuukw case," named after Earl Muldoe [8], a master carver from the Gitxsan Nation renowned for his bentwood masks, totems, and boxes. The dispute concerned ownership of over 58,000 km² of land in northwestern British Columbia, land threatened by logging operations. In 1997, the case was heard in the Supreme Court, where, for the first time, oral histories were accepted as admissible evidence of ancestral occupation of the land. In the end, the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en won the case.

However, in line with previous rulings, the Court established various criteria that restrict Indigenous control over their territory. The judges ruled that "Constitutionally recognized aboriginal rights are not absolute and may be infringed by the federal and provincial governments if the infringement furthers a compelling and substantial legislative objective". These "compelling and substantial" objectives are none other than the continuation of the economic activities on which the Canadian economy has always relied: "the development of agriculture, forestry, mining and hydroelectric power". Not without irony, it also includes the "protection of the environment or endangered species".

Another weakness of the Delgamuukw ruling is that Nations must claim exclusive occupation of the territory. However, the territories of various Nations often overlapped, making the European conception of borders somewhat irrelevant [8]. Finally, the Delgamuukw decision did not grant constitutional protection to titles considered "extinguished" under Canadian law prior to 1982. In other words, only areas left vacant (undeveloped) by the Crown or third parties could be claimed.

Today, in the absence of a clear definition in the Constitution, the question of Indigenous rights remains unresolved and continues to evolve through the decisions handed down by the Supreme Court.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

In 2000, after 25 years of negotiations following the Calder affair, the Nisga'a Nation and so-called British Columbia ratified an agreement that granted the Nation self-government and control of 2,000 km² of its traditional territories. This marked the first modern treaty signed in the province. Reserve lands were returned to the Nisga'a as collective property and placed under the governance of the Nisga'a Lisims, the Nation's central authority [12].Then, in 2013, the Nisga'a Nation became the only First Nation in the country to privatize its lands, allowing its members to purchase land within its territory. In the context of this newspaper's main subject, it should be noted that the Nisga'a are co-owners of the Ksi Lisims marine terminal, which exports natural gas to Asia. This is where the PRGT pipeline is to terminate, with the Nisga'a Nation partnering with Texas-based Western LNG in the project. While there are dissenting voices within the Nisga'a, it is hard not to be cynical and see in these developments the culmination of successive efforts by colonial governments to eliminate Indigenous exceptionalism and clear the way for extractive industries.

In so-called Quebec, the James Bay Agreement, involving the Eeyouch, Naskapi, and Inuit, was the first modern treaty. Legal action was taken against the provincial government in the 1973 Malouf ruling to halt the construction of the La Grande hydroelectric complex and force negotiations. Additionally, for the past four decades, the Inuit (see the text Band Council vs. Hereditary Chiefs) of Essipit, Mashteuiatsh, and Nutashkuan have been negotiating with both levels of government to define their territorial rights in an agreement known as the “Petapan Treaty”. The exact contents of this treaty remain unclear, as discussions are being held behind closed doors, but all indications suggest that the government’s objective is to eliminate or at least suspend Indigenous title. For the Mashk Assi collective, which is mobilizing against the treaty and the hold of band councils in local politics, “self-government” and promises of “co-management” serve as a façade for the ongoing dispossession by the Canadian state. The state’s objective remains, as always, to secure access to territory and the exploitation of “natural resources,” which necessitates the erasure of Indigenous sovereignty. In Innu law, Land is inalienable and constitutes a legacy for future generations. Moreover, signing the treaty would lead to the “municipalization” of Innu reserves, consolidating the authority of band councils—an imposed governance model—at the expense of the traditional political structures that the collective is striving to revalorize.

The same debates are unfolding in Indigenous communities across Canada. Over the past two decades, the Tsawwassen and Maa-nulth First Nations have reached agreements with the British Columbia government, while the Gitxsan are still negotiating with the province. The new chapter of resistance that is emerging with the fight against the PRGT serves as a reminder that, without a balance of power built by Indigenous activists, these negotiations often favor the State, which, in the process, disguises its colonial nature under the guise of reconciliation and partnership. As for the Canadian justice system, when it has deviated from the status quo, it has always preserved the interests of the State—whether by reducing Indigenous political claims to matters of land interests, or by introducing various conditions that allow companies and governments to continue business as usual. It remains unproven that “consultation” processes and other compromises serve anything beyond the interests of those who exploit the land. Given the inadequacy of legal strategies, do we have any choice but to rely on our own resources?

[1] Unrestricted, unshared, and not extinguished by the passage of time.

[2] As Mailhot and Vincent put it, “The link to the land is thus conceived as one aspect of the relations of power and control that exist in the universe [e.g., between animal masters and the species they control, or between a boss and his employees]. It is therefore a political concept [...] [which] corresponds, not to our concept of property, but to that of sovereignty.” This clarification is important, as it emphasizes the Innu's right to their territory, Nitassinan. What is crucial to remember, however, is that Western legal concepts often fail to accurately describe the nature of the ties between Indigenous peoples and Land.

[3] In contrast, Canadian liberal inheritance law grants full owners three prerogatives: 1) usus, the right to use the property as one sees fit (in accordance with the law); 2) fructus, the right to enjoy the property, i.e., to earn income from it; and 3) abusus, the right to dispose of the property, by selling it, giving it away, transforming it, or even destroying it.

[4] As Overstall explains, Gitxsan kinship can be understood as a system for ordering, interpreting, and relating to the world. Like science, it is a form of knowledge. It is this rationality inherent in kinship systems that allows it to serve as the foundation for legal relations within the nation.

[5] Greer points out that this process goes hand in hand with the development of the State: courts and governments create and administer property titles, while these new property relations necessitate the creation of courts and governments.

[6] In private law, the term “fiduciary” refers to a person responsible for the custody and management of property belonging to another. Based on the paternalistic Indian Act, the Supreme Court has ruled that the Crown has a “fiduciary duty” towards Indigenous people and the lands “ceded” to it. In other words, under Canadian law, Indigenous peoples are considered “wards” of the State. One of the ways in which the State “watches over” Indigenous people is by granting them residency rights on its lands, namely on reserves. Legal language is filled with such far-fetched concepts, which obscure the colonial nature of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian state.

[7] For a more in-depth discussion of the parallels between primitive accumulation in Europe and America, see the introduction to Peau rouge, masques blancs by Glen S. Coulthard, and W. C. Roberts' article, "What Was Primitive Accumulation? Reconstructing the Origins of a Critical Concept," published in the European Journal of Political Theory (2020).

[8] It was the Bagot Commission (1884) that recommended allowing Indigenous peoples to participate in the land market. The underlying idea was that collective ownership hindered the development of an entrepreneurial spirit and a sense of responsibility, arguing that individuals would value what they owned more. Today, we can see just how misguided this view was.

[9] The Nisga'a live in the Nass River Valley in northwestern British Columbia, a territory that overlaps with that of the Gitxsan. The two Nations share many traditions, and their languages are closely related.

[10] For example, in the Van de Peet case (1996), which was criticized for its narrow—and arguably backward-looking—definition of Indigenous rights, limited to cultural practices that predate contact with Europeans, the Supreme Court ruling stated that an Indigenous right "is determined through the process of determining whether a particular practice, custom or tradition is integral to the distinctive culture of the aboriginal group".

[11] Delgamuukw is one of the names passed down through generations to hereditary Gitxsan chiefs. Three different chiefs bore this name during the 13 years the trial lasted. When the claim was filed, Albert Tait was Delgamuukw. Upon his death, Ken Muldoe succeeded him. Ken was the hereditary chief when the initial trial began in 1987. After Ken’s death, Earl Muldoe carried on the name until the Supreme Court proceedings were completed.

[12] These lands, which do not encompass the entire ancestral territory (and whose boundaries are disputed by the Gitanyow), are held by the Nisga'a in “fee simple,” a common law category that bears little resemblance to their traditional relationship with the land. This ownership status also implies that the federal and provincial governments retain certain legal authorities. For instance, it remains the responsibility of the federal government to decide whether or not to issue environmental permits for the construction of infrastructure, such as the gas terminal at Ksi Lisims.

For those who wish to explore further, here are a few suggested texts that were used to document this article:

- Red Skin, White Masks: Against the Colonial Politics of Recognition by G. S. Coulthard (2018)

- Property and Dispossession: Natives, Empires, and Land in Early Modern North America by A. Greer (2018)

For shorter texts, consider the following:

- “‘Property’ and Aboriginal Land Claims in the Canadian Subarctic: Some Theoretical Considerations” by P. Nadasdy (2002)

- “Le discours montagnais sur le territoire” by J. Mailhot and S. Vincent (1980)

- “Encountering the Spirit in the Land: ‘Property’ in a Kinship-Based Legal Order” by R. Overstall (2005)

- “Colonial Reading of Recent Jurisprudence: Sparrow, Delgamuukw, and Haida Nation” by G. Christie (2005)